A New Kind of Transitional Stay

Hello! It's been a while - due to American politics, personal issues, and other factors, I just haven't had the energy to spend on historical sewing or writing about fashion (beyond what I do for AskHistorians; link to my profile if you'd like to read some short articles on a variety of social history topics) - but last month, I attended the 2018 CSA Mid-Atlantic/Southeastern Biregional Symposium in Shippensburg, PA. It was quite a trip! I was so happy to meet up with so many fashion history scholars, and particularly to meet Ann Wass (of Riversdale House Museum), Mackenzie Anderson Sholtz (of Fig Leaf Patterns), and Lydia Edwards (author of How to Read a Dress). You can see all of my photos of the exhibition at the Shippensburg Fashion Archives and Museum on Instagram! I delivered a paper of my own, which I hope to turn into a podcast episode/blog post soon, but what really thrilled me was the presentation Mackenzie gave, "A Transitional Corset and its Companion Gown c.1804 from the Collection of the DAR

Museum".

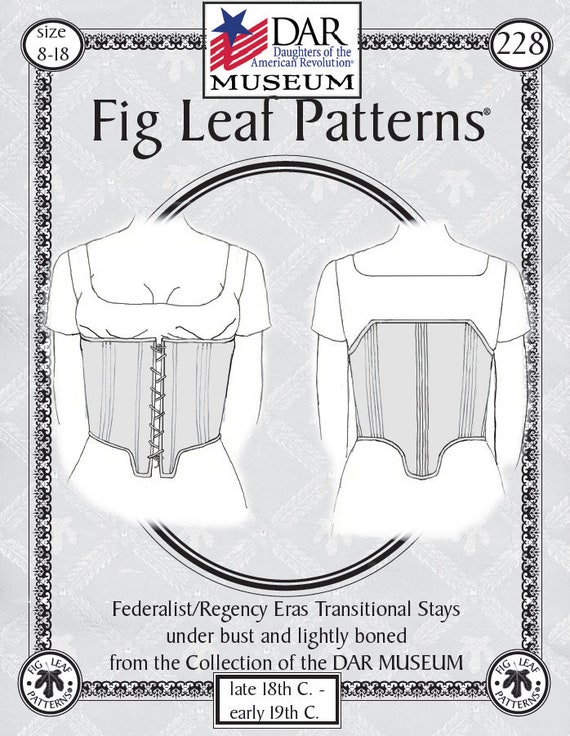

Said transitional corset is available as a pattern from Fig Leaf, for illustration.

At first, I was interested because it was based on actual garments and their construction, and because Mackenzie is an authority on that kind of thing, and because you know that transitional period is kind of my Thing, but when I was watching it, I realized that I recognized these stays - although not this particular version.

In 2011, I visited Historic Cherry Hill, a home once owned by the Van Rensselaers in Albany, NY, to do research for my qualifying paper (thesis). I came across this pair of very plain stays that have confused me ever since.

Said transitional corset is available as a pattern from Fig Leaf, for illustration.

At first, I was interested because it was based on actual garments and their construction, and because Mackenzie is an authority on that kind of thing, and because you know that transitional period is kind of my Thing, but when I was watching it, I realized that I recognized these stays - although not this particular version.

In 2011, I visited Historic Cherry Hill, a home once owned by the Van Rensselaers in Albany, NY, to do research for my qualifying paper (thesis). I came across this pair of very plain stays that have confused me ever since.

Best of all, a set of front and back lacing strapless mid-18th century stays. Sounds ordinary, yes? But they're made from two layers of unbleached linen with no visible seam allowances. The pieces in both layers are were put together, and then the seam allowances were turned in and sandwiched between the layers; the pieces were then butted together and overcast, leaving a flat, clean seam. The front and back pieces were cut with the lacing edges on the fold. AMAZING! (They're also not fully-boned - the channels are in groups of two to five.)

(from "Museum Visit - Historic Cherry Hill", 11/8/2011)

I originally cut the front too high - or the rest of it too low (but I'm short-waisted so it worked out all right for me). Not sure how it happened. But it was an easy fix! These don't have a lot of boning, unlike the stays most people make, but these are a reproduction of a pair at Cherry Hill, so I'm pretty sure it's period. The curved channels ought to straighten out and overlap with the addition of boning, but I might need to take out the stitching and make the curve more gradual.

(from "50% Backstitch Completion!", 2/21/2012)

My stays are comfortable enough, but they don't have enough of a lacing gap and I seem to have some kind of mental block when it comes to bust:waist proportions (I really ought to be getting a more hourglassy figure).

(from comment on "Curtains, and Patterning Update", 9/26/2012)

The shapes of all the pattern pieces are so quintessentially eighteenth century, but the overall shape of the stays is basically a tube. Even when I scaled it up and enlarged it to fit me, trying to get it to not be a tube was a struggle - and they were so short in front, even though the back fit. The boning was also weird, not just the normal half-boning of Diderot-style stays but completely vertical in the front.

|

| You can see that I tried to make the front disproportionately high at one point before deciding that was too far from the original |

In the end, I never found them satisfactory. They didn't come up to the proper height at the bust, and when I tugged them up they left my stomach completely unmanaged. They just didn't give me the right shape. Who knows what's wrong with them, I thought, and set them aside.

Well, Mackenzie's contention is that during that late 1790s-early 1800s transition period, many women wore stays that hugged the ribcage, pushed up the underbustline, and created tension with the shift to provide a certain amount of support for the bust without either the actual cups of 1810s-style corsetry or the conical shape of 1780s stays. (The bodice linings that pin at center front, which are so common during this time, then provide another light layer of support and coverage. People have been speculating for some time that these linings were used as the only bust support, which I never fully bought - but being supportive in conjunction with something else does make sense.) You can recognize them by how low-cut they are in the front, and that vertical boning.

These (above) from Historic New England might be the same type, and these from the Philadelphia Museum of Art are too.

As I was watching the presentation, it hit me that this is what I made back in 2012! Unknowingly, I had reproduced a set of transitional stays and tried to use them for a purpose they weren't designed for, which is why they failed so badly at it. I could have used these for my thesis project instead of trying to engineer my own version of the famous V&A short corset.

I tried on my version of the stays with the rest of the 1790s outfit I made for the project, and was delighted to find that they worked perfectly.

This silhouette is quite in line with what we see during the transitional Neoclassical era.

Because this was something of a make-do, there seems to be more variation in construction than there is with earlier stays and later corsets. There's a lot more to learn about it!

| "The Artist's Wife", Louis Leopold Boilly, 1795-99; Clark Art Institute 1955.646 |

| "Mrs. Martha Hubbard Babcock", Gilbert Stuart, ca. 1806; Clark Art Institute 1994.14 |

Fascinating! For comparison, do you think the 1795-1805 short stays in your book (with their slightly higher front, and diagonal boning) supported the bust fully, or that they were an in-between semi-supportive style?

ReplyDeleteMaybe in-between! The front seems too high to be underbust but too low to be really supportive.

DeleteOn the other hand, I was peering at the illustration that goes along with those stays, and it seems to depict a woman wearing underbust stays. You can distinctly see her entire bosom above the top edge. So at least now there's visual evidence!

That is SO interesting! I think that second portrait really shows what you're talking about. There's a pretty hard line under the bust that seems to be squeezing up the bust, which is supported by other layers. Thanks for sharing all this info! I love it!

ReplyDeleteDefinitely! When I look at 1800s portraits now (vs. 1810s or 1820s), I'm noticing the different profile in a lot of places. Pretty cool, and it's giving me way too much inspiration!

DeleteI am not seeing any of these as necessarily underbust. On someone with a torso as short as mine, they'd fit as ordinary bust supporting stays. I would like to see good evidence that underbust stays were a thing, like say a Rowlandson cartoon, before I'd believe this hypothesis is even a possibility.

ReplyDeleteHi there, Sharon! I seem to have missed this comment years ago, unfortunately. I actually have an extremely short torso - about 12-13" from the bottom of my neck to my waist - which is what makes me convinced that they're intended to be worn under the bust. These stays I made as replicas of the original (ie with the same dimensions) are actually slightly too long and lengthen my waist a little bit, which is what I'd expect of underbust stays made for someone with more normal dimensions. And as I noted in the blog post, I tried to wear them as ordinary stays a few times and found them way too short and way too cylindrical to work that way.

DeleteIt would be nice to have direct visual evidence of how these were worn in the form of fine/genre art or a cartoon, but I think most the dressed portraits of the period show a bust profile that, frankly, could not be achieved with the typical inserted-triangular-gusset form of Regency corset.