AMBA: The Recent History of Mourning

This episode took me forever to write. I was originally going to start with a blog post I wrote a few years ago, relying on primary sources on mourning from the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. Then, as I started to go through it, I started to reinterpret a number of the primary sources, and then I came across Lou Taylor’s book, Mourning Dress: a Costume and Social History, and I realized that I needed to fully read it and regroup. So. (This is the transcription of the episode, for those who prefer reading to listening, or want to go back and double-check something they heard.)

Funerals and mourning goods seem to have become status symbols in Europe in the late Middle Ages, when royalty and the upper aristocracy began to indulge in long funeral processions with large numbers of mourners and horses in black draperies. Male mourners would wear loose gowns of crape, with old-fashioned hoods; women wore ordinary but plain gowns. Black was fairly common as a mourning color, but brown and white were also used. Widows added to this a white barbe, something like the wimple, obsolete by then, a cloth which loosely covered the neck and upper chest, and a kerchief draped over their heads. This kerchief took on a particular drape over the forehead, curving down in the center, in the 15th century, which would become a standard shape for widows’ veils and caps. Widows were of particular interest to mourning codes, and continued to be until mourning stopped being a Thing in the 20th century: there was always a lot of tension between the ideal widow, who remained in unfashionable mourning forever to mark that their status as a wife had ended, and the often more real widow, who sometimes wore black fashionably or left off mourning at some point, perhaps in order to remarry.

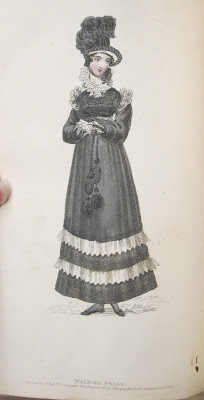

Walking dress and evening dress in the general mourning for Princess Charlotte, La Belle Assemblée, Nov. 1817

Funerals and mourning goods seem to have become status symbols in Europe in the late Middle Ages, when royalty and the upper aristocracy began to indulge in long funeral processions with large numbers of mourners and horses in black draperies. Male mourners would wear loose gowns of crape, with old-fashioned hoods; women wore ordinary but plain gowns. Black was fairly common as a mourning color, but brown and white were also used. Widows added to this a white barbe, something like the wimple, obsolete by then, a cloth which loosely covered the neck and upper chest, and a kerchief draped over their heads. This kerchief took on a particular drape over the forehead, curving down in the center, in the 15th century, which would become a standard shape for widows’ veils and caps. Widows were of particular interest to mourning codes, and continued to be until mourning stopped being a Thing in the 20th century: there was always a lot of tension between the ideal widow, who remained in unfashionable mourning forever to mark that their status as a wife had ended, and the often more real widow, who sometimes wore black fashionably or left off mourning at some point, perhaps in order to remarry.

We know something of what was considered normal in mourning at this time because of sumptuary legislation. Sumptuary laws, if you’re not familiar with the term, are laws regarding what people could or could not wear: usually they were enacted because the upper echelons of society were concerned about a rising middle class or lesser nobility having the means to look like they belong to the upper aristocracy or even royalty. Margaret Beaufort, the famous mother of Henry VII, issued a very helpfully detailed set of sumptuary laws dealing with funeral mourning in the years around 1500 to prevent people who weren’t seen as entitled to make this huge display. From them, we can see that aristocratic women were wearing loose overgowns made excessively long, so that the hem trailed in back and had to be draped over the arm or belted up in front. They also wore a cape with a hood, which had an old-fashioned liripipe on it (just like men’s mourning hoods) – it’s hard to do this without images, think of the stereotypical medieval hood, coming to a long, long point in the back – that point is the liripipe. These sumptuary laws regulated the lengths of gowns and liripipes in order to prevent individuals from a lower rank challenging those in higher ones in terms of extravagance: the queen’s could be the longest, followed by duchesses, and so on. All these things, it needs to be said, were specific to mourning worn for funerals: outside of that, more ordinary black clothing was worn – because by this point, black had become the predominant color for mourning, with brown hanging on among the poor.

Outside of funerals, people started off with first, full, or deep mourning, where luster was avoided: black wool broadcloth and black crape were worn, without jewelry. All parts of dress were affected, apart from the shirt/shift: hatbands, gloves, stockings, swords, buttons had to conform. Second mourning allowed at least white touches and silk fabrics, and it was followed by half-mourning, which was even less overpowering. That said, not every mourning period involved progressing from first to half-mourning – for certain levels of relations, one might only wear half-mourning. And overall, these stages were different lengths of time for different relatives.

There was also “court mourning”, which was worn by anyone in attendance at court, usually for foreign monarchs related to the king and queen or for members of the royal family. (The king himself wore purple for mourning.) And there was “general mourning”, which was worn for deaths in the royal family by anyone in the country. The fact that members of the middle and working classes would dress in black during a general mourning irked the lesser aristocracy, but that had little effect.

Do these rules sound familiar to you? They’re a basic framework that mourning would continue to follow through the centuries, and the basis of the rules that we now think of as specifically Victorian – but they aren’t. They seem to come about in the early modern era.

Here’s a Restoration-era example:

Samuel Pepys, 8 December 1667

and so to White Hall, where I saw the Duchesse of York, in a fine dress of second mourning for her mother, being black, edged with ermine, go to make her first visit to the Queene since the Duke of York was sick

The duchess of York was born Anne Hyde; her mother, the Countess Frances Aylesbury Hyde, died at the beginning of August in the same year.

Over the course of the 17th century, funeral mourning started to come into line with fashionable dress: the men’s mourning gown was replaced with a mourning scarf tied across the body like a sash (black for a male deceased, and white for a woman or child) and a mourning cloak, and the hood was replaced with a hat, the crown of which was wrapped with a crepe band, tying in the back so that the long ends hung down behind. Women ceased wearing the loose, trained gown and wore fashionable mantuas of black wool, and widows wore enveloping caps rather than kerchiefs and fashionable white neckwear instead of the barbe. And at the same time, the laws regulating funeral dress were losing effect and mourning slid down the social scale to be available to all who could afford it.

One of the earliest comprehensive set of mourning rules I have seen is from Antoine Furetière’s 1727 French “universal dictionary”. I’ve filled it in here with more details from a few legal sources from the 1730s and from a book on death traditions in France, Le necrologe des hommes célébres de France, from 1767, in order to reconstruct the general framework of mourning in France at the time. We can’t assume that these customs were the same in England and America, but there are a number of aspects of these French rules evident in descriptions of mourning from the 18th and 19th centuries, so I think it makes more sense to assume that there’s a lot of crossover.

Greater mourning – worn for a deceased parent, grandparent, parent-in-law, sibling, or spouse, or for a general mourning – was split into those three stages: wool, silk, and little mourning, which translates to deep, second, and half-mourning in English. The first stage, wool mourning, consisted of plain clothing made of black wool with white linen fringes, black wool or silk stockings, bronze shoe buckles, ruffles (and kerchief and cap for women) of white crepe or wide-hemmed white batiste, and, earlier in the century, an ankle-length black mourning cloak. However, a widower paid for his own mourning clothes. Men in deep mourning wore crepe trim on their hats; they also wore “weepers”, flat white bands sewn to their cuffs. English sources reported that men in hotter colonies wore red wool coats with black cuffs and buttonholes instead of regular full mourning.

Second mourning was a little fancier, with silk allowed as well as wool, white gauze sleeve ruffles (and kerchief) with pinked fringed edging.

Half or lesser mourning could be mixed black and white or all white for women (some English sources put all white as a second mourning dress), with white stockings, a plume in the hat, and blue, black, and white ribbons or embroidered gauze trim. Typically, children only went into half-mourning, often in white gowns with black sashes, in order to keep from distressing them too much. In France, when half-mourning was the only type worn, it was usually referred to as “black and white mourning”, as it was broken into a black stage and a white stage.

When in mourning for parents, the rule was recorded as three months of deep mourning, in which men wouldn’t even wear coat buttons; three weeks in, men could wear coat buttons, and six weeks in, one could wear jewelry with black stones. This was followed by six weeks of “silk mourning”, where one could wear diamonds and silver buckles, and then six weeks in half mourning.

For grandparents, deep mourning was worn for six weeks, then second for another six weeks, and half mourning for the last six. For brothers and sisters, it was deep mourning for one month, second mourning for fifteen days, and half mourning for fifteen more days. Uncles and aunts only required second mourning, and cousins half mourning.

Widowers wore mourning for their wives for six months. As with parents, they went in deep mourning without buttons at first (for six weeks); then six weeks with coat buttons and silk stockings; six more weeks with silver buckles; and the last six weeks in half mourning with white stockings.

For widows, the requirements were more stringent. The full term of mourning was a year and six weeks. For the first six months, widows wore a long, full wool gown held in with a black crepe belt, with the train tied up on the sides; for the next six months, black silk with white crepe and black stone jewelry; and for the last six weeks, half mourning of black and white, but never just white, with embroidered gauze. Widows also wore a black band around their caps, which featured especially dense ruffles on the side of the face, and a crepe veil or black hood. Their mourning gear was provided by their husband’s heirs, and they were not supposed to remarry during the full term out of respect for their husbands.

Servants were not required to be dressed in mourning, although an employer could outfit them in it as a status symbol; in some cases, that, like putting black drapery on one’s coach, was restricted to the aristocracy by sumptuary laws.

The only aspect of French mourning customs that I’ve seen specifically called out by the English as not belonging to their system is that under these rules, if you inherited from someone you wore mourning longer – apparently in England, and probably in America, inheritance made no difference to your mourning status.

These traditions changed little, if at all, by the early 19th century. When the rules were printed in the 1826 French National Almanac, for instance, they were exactly the same as the ones I rattled off before. The one change I’ve been able to document is that purple, which is now known as a second or half-mourning color, seems to first appear in print in this context around this time – as far as I can tell, in the November 1824 issue of La Belle Assemblée, where the “Costume of Paris” section states that Parisian women were wearing violet pelisses instead of black (along with other colorful touches) as mourning for Louis XVIII wound down.

Lavender doesn’t seem to come about until a few years later. Following the death of George IV, the former Prince Regent. The Ladies’ Museum wrote in August 1830, a few months into the general mourning,

“The remark has been repeatedly made, that the mourning for our late most beloved and regretted sovereign, though general, was by no means so deep as the occasion called for. We admit that if Fashion could be expected to stand still, this remark would be just; but in mourning, as in everything else that relates to the toilet, changes are continually taking place. We appeal to those of our fair readers who recollect the fashions during the last seven years, whether they have not observed the most striking innovations even in the deepest mourning? Let not our British fair then be charged with a want of respect to the memory of their late beloved monarch, because in many instances their dresses present a mixture of lavender, grey, or white with black; this mixture is now recognized as mourning, and consequently, though less sombre than the mourning of former days, it must still be considered the garb of woe.”

The big issue here is that people were wearing second or half mourning rather than full mourning for their late monarch; that lavender is tossed in the list with the others implies that it’s established as a second or half-mourning color by this point. It’s interesting to me to see that in the first month after George’s death, the “Mourning Fashions” in the Ladies Monthly Museum are described in elegant detail, and includes plenty of white, grey, and lavender touches – but in the same magazine, the first month after his daughter, the beloved Princess Charlotte, died in childbed in 1817, the descriptions for dress are very spare, with everything black; anything not black is white. The same contrast is shown in La Belle Assemblée, and it’s pretty telling of the difference in feeling on the deaths of both people. Anyway, it seems like lavender and purple became a regular part of the mourning system between 1820 and 1830, sometimes as second mourning and sometimes as half.

It’s difficult to know how much English rules reflect American standards. The only written American customs I’m aware of, printed in The Knickerbocker Magazine in 1840, are very different from British ones: a year of deep mourning for a parent, nine months of deep mourning for a sibling, three months of second mourning for an uncle or aunt, six weeks of second mourning for a grandparent, and a few weeks of half-mourning for an in-law or cousin. It’s possible that this reflects real practices, but on the other hand, it’s one list that disagrees strongly with all the others I’ve seen, and it’s in the context of an article complaining about the practice of wearing mourning. So personally, I think it’s either deliberately misleading – it’s generally harsher than the older codes, and it doesn’t use the stages progressively, with deep, second, and half mourning worn during one mourning period – or it’s written by a man who didn’t have to pay as much attention to the details and was unaware of the code in full. (All the codes I’ve seen pay more attention to women’s dress in general.)

But either way, the mid-19th century is when the etiquette books do start to speak about mourning in more detail and sometimes differ between themselves, all of which is often mistaken as the beginning of mourning customs. It should already be pretty clear, because I’ve talked for however long now about this system of distinct mourning stages, that that’s not the case. Deep mourning was not a Victorian invention, widows spending a year in mourning was not a Victorian invention, having a system of progressive stages of mourning was not a Victorian invention. It’s often said that there was a Victorian “cult of mourning” stemming from the death of Prince Albert in 1861, but I like to say that there was actually just a Victorian cult of etiquette books.

Although more broadly, what we’re seeing is just the effects of the Industrial Revolution on a social practice, which come together to make it look like there was a mourning mania when they weren’t actually wearing it longer or more fanatically than before.

Mourning was a decent market for industrialists and entrepreneurs, so they introduced more varieties of dull black wools and silks, and more mourning-specific accessories to advertise to the public. In the general mourning for Princess Charlotte in 1817, fashion magazines stuck to recommending wool broadcloth, crape, and bombazine, trimmed with gauze, muslin, or crape. In the 1870 Art of Dressing Well, by contrast, deep mourning could be made of serge, bombazine, delaine, barège, Empress cloth, and non-lustrous alpaca; other options not given there were paramatta, raz de St. Maur, and cashmere.

More people rising to the top of the middle class or lesser nobility through trade meant that there was a need for instruction books on basic customs those born to that rank grew up learning, like paying calls and dressing in mourning. With the increased amount of text written about mourning, more disagreements about the appropriate lengths of time to wear the various stages (and where exactly purple and lavender come in) cropped up. This, plus a lot of writing about how people shouldn’t wear mourning when they’re not actually feeling in need of it or about people leaving off mourning with unseemly haste, are indicators that none of the lists set down in print are 100% accurate with regard to actual practice. Most likely some individuals would pick a book and scrupulously follow the instructions in it, and others would stick to a basic guideline but follow their gut as to when exactly to switch from deep to second mourning, and second to half, and, of course, everything in between. Most American sources were pretty up-front about this, while still giving set periods (sometimes specifically given as “the English standards”) to broadly guide readers.

For instance, the 1889 American Etiquette and Rules of Politeness stated “In the United States, no prescribed periods for wearing mourning garments have been fixed upon. When the grief is profound no rules are needed. But where persons wear mourning for style and not for feeling there is need of fixed rules.” Etiquette: An Answer to the Riddle, When? Where? How?, published in Philadelphia in 1893, explains that “it is generally conceded that it is more respectful to wear plain black than to appear in colors during the months immediately following the death of a near relative The length of time that mourning dress should be worn is a matter of taste, but it should not be laid aside too soon, as though the wearing were an unpleasant duty, nor should it be worn too long, for the sombre robe has a depressing effect on others, especially invalids and children,” and then goes on to give rules for people who want them.The Dry Goods Reporter, in 1902, went so far as to say that “there is no period in a woman's life where so much is left to her own discretion as in the period of mourning. Her individuality is allowed to modify generally accepted rules.” That being said, when giving examples of ways that women could individualize mourning, they don’t tend to say anything very extreme, so we’re probably not talking about really significant deviations from the rules.

While the stages of deep, second, and half-mourning continued to be ordered by etiquette books through the 1940s, and general mourning was even worn in Britain for the death of Edward VII in 1910, those books also give the impression that people were becoming impatient with mourning standards in everyday life. For one thing, there’s often a lot more tsking at people who wear “sloppy” or “flashy” mourning – who pay attention to the letter of the law but not the spirit. Black armbands in place of any other signs of mourning also come in for criticism; these started as mourning touches for men in uniform who couldn’t really comply with the rules overall, but by the turn of the century etiquette books conspicuously frowned on the practice of everyday people thinking them adequate. There’s also evidence that the stages of mourning were simplified: Everyday Etiquette in 1905 recommended deep mourning for a year for all deaths in the immediate family, and 3-6 months for in-laws, while Emily Holt’s Encyclopedia of Etiquette, 1921, recommended a year of deep mourning for immediate family members, a less-deep mourning of three months for extended family and a month and a half or so for parents-in-law. So the popular wisdom that mourning became less entrenched as the twentieth century went on is true, but it really doesn’t seem like there’s a big shift following World War I, at least in terms of what was recommended and considered the most socially appropriate. It’s not until after World War II that etiquette books stopped telling people that they should wear black for any significant period of time, which I suspect has as much to do with the overall changes in society between 1900 and 1950 as it does to do with wartime deaths.

So, I think there’s a fascination that people have with mourning as an archaic, obsolete rule as a result of that modernization, to the point that it actually becomes a kind of fetish. Which seems like part of the reason people will identify all black clothing from the past as mourning clothes, despite the fact that just like today, black could be worn as a fashionable choice: as early as the 1849 Etiquette of Fashionable Life, we’re told that “some ladies prefer black dresses to any other. In such cases, they can trim them with what colours they choose, but the etiquette of the ballroom requires that mourning black should be trimmed with scarlet,” and by the 1870s it was becoming normal for middle-class women to have a “best black dress” that would get them through a number of different social situations.

At the same time, there’s an opposite impulse – people are also repulsed by the concept of mourning dress. Probably some of that is the general negative opinion people have of Victorian customs and dress standards, which are seen as restrictive and unnatural. But I think we can also blame Gone With the Wind. Both the book and the movie were wildly popular, and shaped the image of the 19th century in a lot of people’s minds. Scarlett O’Hara was definitely written to appeal to an audience that saw itself as way more modern than the 1860s setting – there’s a lot of early 20th century pop culture that was used to draw a line between the fast, exciting, convenient modern times and what they saw as a staid, stodgy, naive old-fashioned era. So when she reacts with irritation and scorn at being expected to follow mourning customs for the husband she never cared about, and impressively takes a spot on the dance floor in her widow’s weeds, that’s the image and mindset that most people today have of Victorian mourning. And it’s widows in particular that people think of when it comes to this subject, and their mourning that’s treated as emblematic of the whole system. Even Lou Taylor spends quite a few paragraphs attributing women’s eagerness to go along with it to false consciousness – the idea that they were deluded into wanting what was worst for themselves – which is a really outdated way of thinking about women, fashion, and consumerism now. (That said, the book itself is from the 1980s, so.)

But the thing is … most people who suffered a loss were actually sad. Dressing in lusterless black wool, with black gloves and neckwear and perhaps even a veil, made it clear to observers that you were grieving and prevented you from having to put on clothing with incongruously happy associations. While that could be unpleasant – some people want to be distracted by everyday life – for others, mourning dress meant that they didn’t have to deal with an expectation to be cheerful, or figure out how to tell people why they seemed upset. We don’t want to go too far in the opposite direction in assuming that people, particularly women, loved the mourning rules, but it’s important to be directed by the sources rather than our present-day norms.

Mourning dress would have been an ever-present reality of life in the nineteenth century – with the number of relatives that people had, and the number of people one would come into contact with on a regular basis, an individual middle-class Victorian would probably see and speak to someone in mourning very often, and would spend a significant amount of time in mourning themselves. Where to us it’s a really weird practice, and where in fiction it only comes up at thematically significant moments, it would have been a normal part of everyday life.

Remember, patrons of my Patreon get to suggest and vote on future topics of the blog and podcast!

Great post, I learned a lot from it! It's especially interesting that you cover such a long period, and show how mourning developed over the centuries.

ReplyDeleteThe rule about not wearing coat buttons in deep mourning for parents got me thinking. The same passage allowed jewelry with black stones, and diamond and silver buckles, for the later stages, so it sounds like a ban on shiny/fancy materials. One wonders if they really went without coat buttons for weeks, or if metal buttons were temporarily replaced with fabric covered or death head type buttons.

My mother told me once that she wishes mourning customs were still a thing. That it must be comforting to have people visibly know without you telling them that you are grieving, and probably don't want cheery company or conversation. Please leave me (the mourner) alone.

ReplyDeleteI really enjoyed this installment. I do wish mourning customs were still active. I have just lost my second parent 3 weeks ago. Grief is such a roller coaster and comes in waves. It would be really nice when out to feel less self conscious when I get triggered by something or am just having a really sad day.

ReplyDelete