Georges Doeuillet may be the least-known couturier I've written about so far - or perhaps second, after Jenny, since his real name is generally available. The only time his name comes up is in conjunction with Doucet, when the two houses merged at the end of the 1920s. But in fact (let this not be a total shock), he was a more interesting and important figure than his present obscurity would make him appear.

Born in 1865, Doeuillet was part of the same generation as Louise Chéruit, Charles Poynter Redfern, and Jacques Doucet. (That is, the second generation - the first generation being born in the early part of the century, like Charles Frederick Worth, John Redfern, and Edouard Doucet.) However, his start came a little later in life.

Some sources state that he first worked as a business manager for Callot Soeurs, which opened in 1895. It seems likely that he began working there from the beginning, so one has to wonder - what did he do until then? At thirty, he would not have been starting his career with them. And for them to choose him and keep him on, he must have had experience and talent. Perhaps he had been managing another fashion house before them.

|

| "Dress by DOEILLET, 18 Place Vendôme, worn by Mlle Adèle Richer", Le Cri de Paris, November 1899 |

The reason I think it likely that he was with Callot Soeurs from their beginning is that he left fairly soon: by 1899, there are matter-of-fact

references to his own fashion house at 18 Place Vendôme (an address he shared with Victor Klotz,

perfumier under the name Edouard Pinaud, as well as a

solicitor), later expanding into

16 as well. According to a

contemporary source, it was common for couturiers of the 1900s to be first and foremost businessmen, buying designs rather than inventing them. As a couturier of this era, Doeuillet would mainly need "a triumphant

combination of business ability and

beaux yeux", which writers assured us

he had.

Doeuillet was reputed to make extravagant gowns for the ultra-rich, though evidently they were

less expensive than those by Callot Soeurs, and he seems to have been very successful through the 1900s, 1910s, and 1920s, judging by

the numerous highly flattering mentions he received in fashion publications. He licensed several

New York department stores to use his designs, displaying his international appeal while also increasing it.

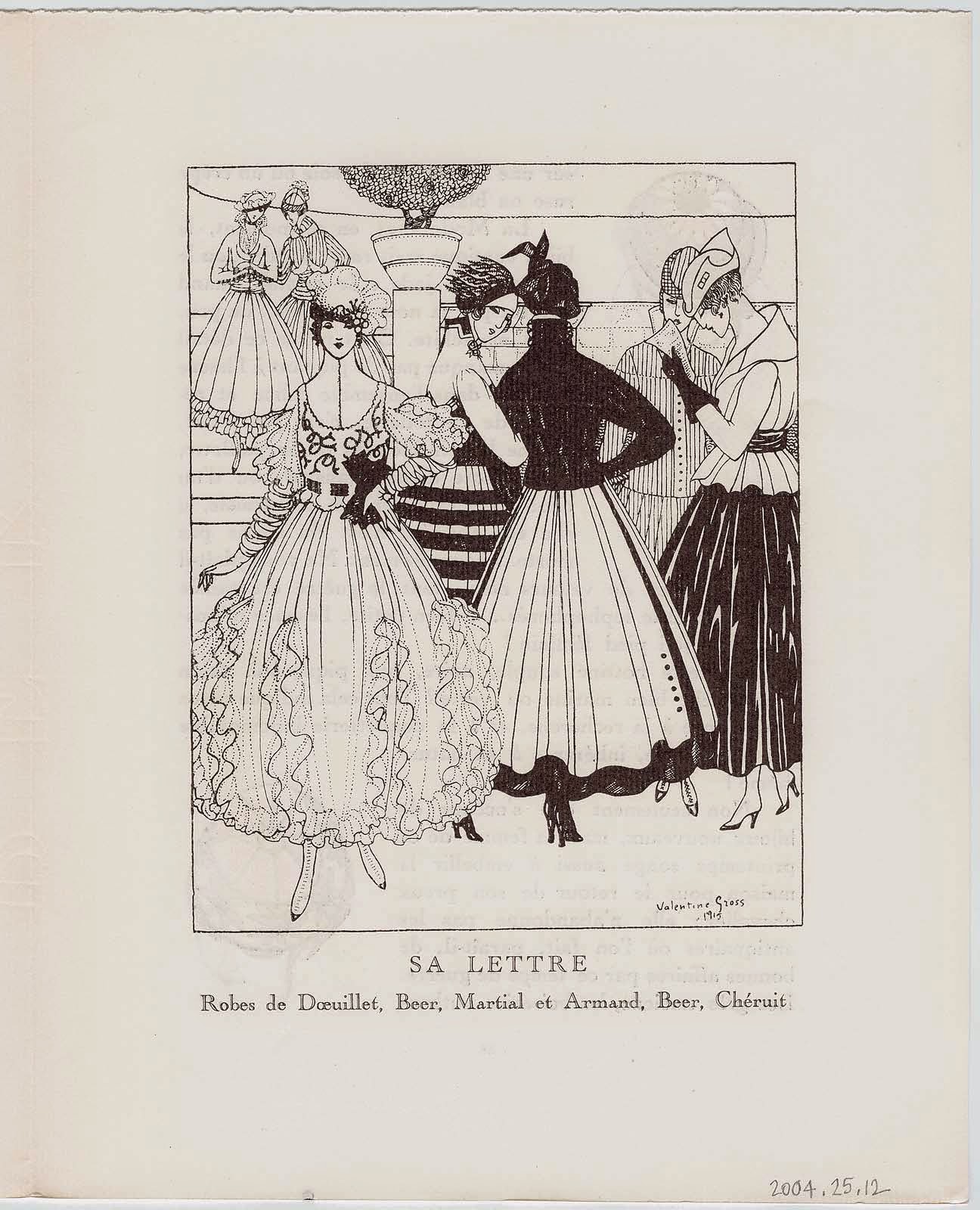

During the 1910s and 1920s, Doeuillet was quite successful. He appeared in the

Gazette du Bon Ton, and can be found getting

long descriptions in trade journals alongside Jenny and listed as a "

celebrated couturier". I don't always give credence to the flattery in fashion magazines, but the wearability and "quiet, distinguished note[s]" given in the

Garment Manufacturer's index does line up with the examples shown in magazines and

museums. The house's style tended towards simple and unadorned elegance.

As I described last week, Georges Doeuillet (by then a member of the

Paris Fashion Board) merged his business with that of the ailing Jacques Doucet around the time of the stock market crash and just before his own death. Under the direction of Georges Auber, Doucet-Doeuillet closed not long after.

There are very few things associated with Doeuillet because of his present obscurity, but one concept I've seen floating around is that he

brought out the first robe de style, that it was later called a cocktail dress, and therefore he invented the cocktail dress. Frankly, I cannot tell where this comes from. Searching Google Books is not a precise survey of fashion texts of the time, but when doing it I can only find

one reference to Doeuillet in conjunction with the

robe de style, and it describes Doucet as the gown's "exponent" and lists several designers making them in 1922.

Part of the trouble is that the term

robe de style is not specific. In French, the term was used from the beginning of the century as part of a phrase, comparable to the 18th century

robe à la -

robe de style Louis XVI,

robe de style Empire, etc. I can also find references to

robes de style without the reference to an historical time period from an early point:

here in 1906 in French,

here in 1903 in English. Unfortunately none are pictured, but from the description, it sounds as though the

robe de style was mainly in the fabric and trimming, less in the cut: Louis XV bows, an open skirt with a lace

tablier, a fichu, and such things.

From the very beginning of the 1910s, the historical era was more frequently dropped, but it seems to have kept the connotation of the

robe de style Louis XVI or thereabouts.

One of 1914 (called in the English translation a gown in "the picturesque style") is described as having a puffy drapery around the hips, as well as short sleeves with lace ruffles. Overall, it was a highly fashionable collection of unfashionable elements - thus the full and long skirt in the 1920s. The style can't be said to have been invented by anyone because it was always present in the early 20th century, a reaction to the increasing speed of modern life and the increasing sleekness and starkness of modern dress.

The term "cocktail dress" does not seem to be extant during this time; "

cocktail party" is only attested from 1928, and it makes sense for the dress name to arise after that. As "cocktail dress" first appears in print in the early

1930s (as far as I can tell), it could have been used as a label by Doeuillet-Doucet, but there's no evidence that it was; likewise, there's no evidence that the

robe de style was considered a cocktail dress. I have to conclude that this is a myth based on garbled half-truths and leave it there.

Comments

Post a Comment