The flamboyant colors of Paul Poiret's pre-war designs and the

theatricality of Bakst's influential costumes for the Ballets Russes

suddenly seemed tawdry and overdone. ... A look of luxury was achievable

through the severity of simplicity. Expensive poverty was the aim.

She dared to suggest that clothes themselves had ceased to matter and

that it was the individual who counted.

The story of the first three decades of the twentieth century can be seen as a narrative of increasing simplicity. Not to continually beat Poiret's drum - no single designer can be held responsible for such a grand shift in style - but his simple black kimono coat, originally introduced in 1903 (itself deriving from the frequent use of orientalism in fashion and interior design in the late nineteenth century rather than springing forth from Poiret's head fully formed) started the general trend in outerwear.

|

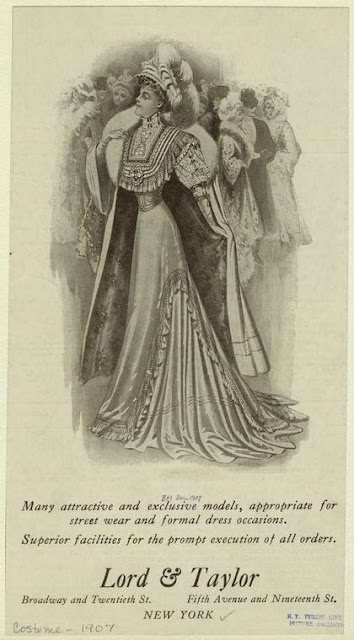

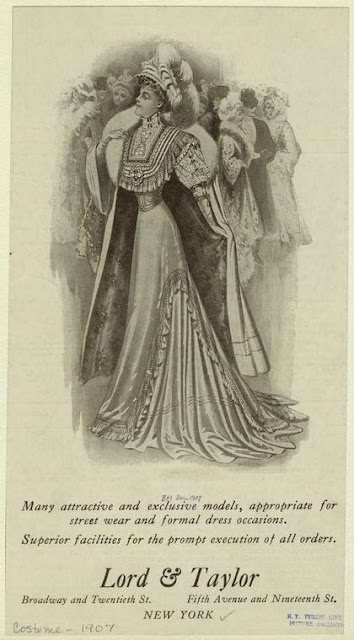

| Lord & Taylor advertisement, Burr-McIntosh Monthly, December 1907; NYPL 816513 |

Other designers followed suit, leading to the incongruous pairing of ornate turn-of-the-century evening gowns in a multitude of frothy fabrics with plain, unshaped, and unstructured evening coats. The columnar coats' success likely led to Poiret's introduction of

the Directoire revival by the end of the decade. While the newer high-waisted fashions could certainly be

heavily embellished and somewhat form-fitting, the overall trend was toward a kind of simplicity that prized rich, relatively unadorned fabrics and their drape, with ornamentation concentrated only or mostly on the bodice. (It must be noted that

unadorned evening dresses were worn by the very wealthy before this point as well, however.)

|

| "Étole et manchon d'hermine des Fourrures Max", Les Modes, 1909; NYPL 818412 |

The shift to a higher waistline also led necessarily to one-piece gowns becoming the norm, which further simplified construction. In general, the turn of the previous century was seen as a time of

great simplicity in dress, and it is clear from Iribe's 1908

Les Robes de Paul Poiret that imitating Austen-era clothing was

the goal.

|

| pp. 2-3 |

But this does not directly contradict Nicholson's claim that Chanel invented simplicity, as simplicity in cut, ornamentation, and color are not the same things, and these

are quite bright colors. What would be more apropos would be to look at Chanel's early years once again, to evaluate her severity and poverty. Did she really advocate a starkly plain, unembellished style?

At the right is a popular dancing frock by Chanel, fashioned from black filet embroidered with black and white flowers and silver leaves. As always with Chanel, the bodice is transparent to yoke depth and the black satin foundation is edged with a narrow band of silver lace at the bottom.

-

Ladies Home Journal, Dec. 1921,

p. 91

The Chanel gown of white crêpe de Chine at right shows Valenciennes edging and a pearl-studded girdle.

-

Good Housekeeping, March 1922,

p. 34

Chanel uses homespun in half inch checks in which browns and all the dull and vivid shades of yellow predominate, combined with blue, gray, or rust. One of these coarse stuffs in tawny yellow and green is especially new and smart ...

-

Harper's Bazaar, January 1922,

p. 49

Mademoiselle Chanel wore a chemise of gold and beige lace arranged in alternate crosswise bands and girdled at the top of the hips. Lovely in color was this frock, worn with many ropes of pearls.

-

Harper's Bazaar, March 1922,

p. 38

Russian embroideries now adorn many of the Chanel corsages: the needlework is often disposed of in crosswise bands on corsage and sleeve alike, and also on the small smart hat. ... The velvet wraps are lined with Georgette crêpe or crêpe de Chine, matching the frock underneath.

-

Harper's Bazaar, April 1922,

p. 140

|

| See below. |

Occasionally Chanel goes in for something as naive and simple as this three-piece costume of gray crêpe made with a straight little frock with an apron that actually has apron strings and two little pockets besides. Incidentally a great many buttons and buttonholes that are not in the least concerned with coming together give the bodice an air of complete detachment.

-

Harper's Bazaar, May 1922,

p. 73

So gorgeous is the embroidery in gold and Paisley colors on this Chanel wrap that only the cut saves it from being an evening wrap. The richness of the fabric (black "Juina" cloth overlaid with silk machine embroidery) is enhanced by the trimming of monkey fur. A chemise dress with sleeves and bodice embroidered to match accompanies the coat.

-

Harper's Bazaar, September 1922,

p. 84

Callot is showing, as usual, her collection of strange, exotic, ever marvelous, embroidered gowns. What a contrast they are to Chanel's gowns! Callot designs the gown to decorate the woman, whilst Chanel conceives clothes from an entirely different angle; the individuality of the woman predominates, the gown is designed as but a background. Although skirts and waists daily grow longer here, Mademoiselle Chanel still remains a delightful exception. She clings to her short and narrow styles, which she herself wears - how well I hardly need say as every one knows her, if only by sight. These suit her youthful type, especially as she generally relieves the extreme simplicity and girlishness of her appearance by adding many gorgeous strings of pearls of dazzling luster. Chanel has succeeded in making simplicity, costly simplicity, the keynote of the fashion of the day.

-

Harper's Bazaar, August 1922,

p. 51

The last quote is quite explicit - vehement, even - in its declaration that Chanel's driving forces were "costly simplicity" and individualism. However, it stands in direct opposition to numerous lavish descriptions of her designs - bright yellows, silver lace, Russian embroidery, monkey fur. Even Chanel's "naive and simple" suit appears a little fussy, and it is covered with non-functional buttons.

How does one reconcile these two opposing viewpoints? For one thing, it is important to note that the last quote is mostly discussing Chanel's own appearance. By all accounts, she did dress in a starkly plain manner through her life, and I'm sure that the description of her in

Harper's (along with the accompanying illustration) was accurate.

For another, one has to consider the fact that "simplicity" is a very subjective term. It's a relative concept, depending on what is seen as ornate or complicated and what is seen as ordinary. Around the turn of the century, "simple" seems to have meant anything

fairly untrimmed, regardless of the complexity of the cut. Similarly, it's possible that what

Harper's calls "simple" is a plainly-cut garment that may or may not be lavishly trimmed or made of elaborately patterned material. Modern clothing has become so simplified (for lack of a better word) that an unqualified use of "simplicity" in a contemporary source implies what appears simple to our eyes, and therefore gives Chanel's work a more modern sheen.

And, in addition to all of this, the context should be remembered. A fashion magazine is not an unbiased, completely factual source. The visual evidence of the illustrations and the descriptions of specific garments from fashion shows are more concrete information for evaluating Chanel's design style at this point in her career.

Comments

Post a Comment