Not Really "Queen Charlotte": Lady Sarah Lennox

Queen Charlotte presented the young George III as a hard-working man with no interest in love or marriage, requiring his mother to seek out a spouse for him to ensure the continuation of the British monarchy. You might be interested to know that the real George in fact sought out his own romance at this stage in his life, with a young woman of the British peerage — Lady Sarah Lennox.

Lady Sarah Lennox was one of the famous Lennox sisters (“famous” if you’re into aristocratic Georgian England, anyway): the daughters of Sarah Cadogan and Charles Lennox, Duke and Duchess of Richmond, Lennox, and Aubigny.

The Duke was the grandson of Charles II via his mistress Louise de Kérouaille; Charles II was a decent father to his many illegitimate children, granting them titles, incomes, and estates to set them up as part of the upper rank of his subjects. Charles Lennox’s father arranged his marriage to the Honorable Sarah Cadogan in a way that sounds quite familiar if you read a lot of historical romances — it canceled out her father’s gambling debt. She was 14 and he was 18, and after the ceremony Charles went on his Grand Tour; when he returned three years later, he found her enchanting from afar and then learned that they were married.

Four of their daughters survived to adulthood: Caroline (1723–1774), Emily (1731–1814), Louisa (1743–1821), and Sarah (1745–1826). All of them played a part in the social scene of their day, but it’s Lady Sarah Lennox we turn to now.

Unfortunately, Lady Sarah’s letters as published don’t begin until just prior to George’s marriage to Charlotte in July of 1761. For the background, we must turn to the stories given by her brother-in-law, the politician Henry Fox, Lord Holland, and by her son, Captain Henry Napier. His account was published in 1837, after his mother’s (and George III’s) death, as part of Fox’s memoir. He claimed that it was what his mother told him, jotted down in his personal papers.

According to him, Lady Sarah became a favorite with King George II as a spunky five-year-old; shortly thereafter, her mother died and she went to live with an older, married sister (Emily Fitzgerald, Countess of Kildare and later Duchess of Leinster) in Ireland. When she was 13, Emily passed her on to another sister - Lady Caroline Fox, later Baroness Holland. Since she was in England again, the king asked for her to come back to court, where he was annoyed that she was now a shy teenager rather than a cute young child. When the king exclaimed, “Pooh! She’s grown quite stupid!” his grandson, the young Prince George, who would have been around 20, began to feel sorry for her. This developed into a romantic attachment.

George III became king a few years later in 1760 and Sarah, now 15, was properly presented at court. This meant that she was now considered “out” in society, a young adult who could be approached for offers of marriage. George began to seek her out at visits and balls, and to engage her in conversations that hinted at his interest in her, although Sarah made sure to firmly keep to propriety. He in fact directly told her friend, Lady Susan Fox Strangeways, that he intended for Sarah to become his queen by the time of his coronation, and shortly thereafter he sort-of-proposed and she turned him down.

In early 1761, Sarah fell from her horse during a hunt and broke her leg and had to stay out of society while it healed. When she returned to court, George was overjoyed, proposed again, and was accepted; rumors about it were everywhere. However, his mother and his tutor, Lord Bute, disapproved of the match because Lady Caroline Fox’s husband was the Whig politician Henry Fox (previously mentioned) - they feared that he would exert influence on George through Sarah. Although George continued to treat Sarah like a fiancée, they convinced him to marry Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz instead.

Sarah and her family only found out that he was marrying someone else with the official announcement. While Fox and others were outraged, Sarah’s pet squirrel had just died, and that turned out to be more important to her than losing the chance to be Queen of Great Britain and Ireland. She was appointed chief bridesmaid for the wedding and a similar position in the dual coronation, which resulted in a partially blind nobleman mistaking her for the new queen, to her embarrassment. While George couldn’t stop staring at his old flame, Charlotte was poised and gracious.

In the end, Sarah had no hard feelings about the matter, except irritation at George’s pretense that they were still engaged even while he was allowing plans to be made for his marriage to Charlotte.

Lady Sarah’s own letters to her friend, Lady Susan Fox Strangeways, tell her side of the story, which feels a little more tart, a little more alive, in comparison with Napier’s my-sainted-mother account. Unfortunately, we don’t have anything about the early stages of the courtship: the first letters are from 1761.

First, on June 19 — a very cryptic one that seems to be discussing how she would be allowed to respond to a proposal, and how Princess Augusta thwarted it. (The ellipses are probably in place of George’s name, as it could have been problematic if letters outright discussing marrying the king fell into the wrong hands.)

Sarah was very much aware of the difficulties of being the object of the young king’s romantic interest. More than that, she was prepared to walk the social tightrope required to marry him. She rehearsed scripts to bring him from vague sweet nothings to an unmistakable marriage proposal, without giving the impression that she wanted one, and she was impatient with the circumstances that prevented it — at the same time, she was unwilling to spend too long on this dance if he wouldn’t pop the question.

Here is the letter from July 7, relating how she learned about the royal wedding:

This is again more interesting than the sanitized family story. Sarah was annoyed that so much of her time had been wasted, and that people at court would laugh at her for having been strung along by the king (or for setting her cap at him in the first place). Her anger comes through, as does her concern for the family’s reputation and her own social standing. It’s hard to fully believe the paragraph about her lack of disappointment, especially given that she was prepared to take him back if he had “a very good reason for his conduct”! But at the same time, there’s a feeling more like someone jockeying for position in a high school setting than playing at the Game of Thrones(tm) or maneuvering to secure her future.

Sarah hoped to be involved in the coronation ceremony specifically to get a good view, though she planned to be freezingly polite to George and his sisters. She accepted the offer of being a bridesmaid, but both her sister Caroline and Lady Susan felt this was a mistake — she quoted Caroline as calling it “mean & dirty”, and she was very annoyed at her for harping on it. As far as can be surmised from her letters, that ended the entire affair for her.

Within months, Lady Sarah received another proposal of marriage, this time from James Hay, Earl of Erroll. (He has an interesting story: his father and his maternal grandfather were both attainted Jacobites, while he fought against his father in the 1745 Rising; he would have had no title as a result, but he inherited one from his mother’s aunt and took her last name along with it.) Although he knelt on the floor and wept, according to her letters, she refused him. Likely the fact that he was twenty years older than her and very freshly widowed played into all of this.

Sarah was not particularly interested in marrying for position, as her ambivalence toward George and Erroll showed. In the end, she married Sir Charles Bunbury, a handsome baronet’s heir with only £2,500 a year — an excellent income for the gentry but much less grand than Sarah was used to. She was 17 and believed herself to be the average age for marrying, so perhaps she felt her time was up and she needed to choose.

While Bunbury courted her with words of love, neither seemed to feel it for the other, and it quickly became unhappy. Sarah sought out affection and flirtation with other men, then embarked on a full-blown affair with Lord William Gordon, brother of the Duke of Gordon, which resulted in the birth of a daughter, Louisa, in 1768. The following year, Sarah and Gordon eloped (with the baby); Gordon soon abandoned her and in 1776 Bunbury obtained a full divorce from Parliament, leaving Sarah in utter social ruin.

But this was not to be the end of her social career. After the divorce, she met the Honorable George Napier, who was finally the loving partner she’d been looking for (as well as her restoration to society). They married in 1781 and went on to have eight children before his death in 1804. She died in 1826, outliving her two youngest daughters.

It seems likely to me that Princess Augusta and Lord Bute would have been looking for German princesses outside of Lady Sarah Lennox’s specific, Fox-related circumstances. There was a rumor around the time of Sarah’s accident that a marriage was being arranged with a princess of Brunswick (probably Elisabeth or Augusta of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel), but Henry Fox “had it from good authority” that it wasn’t the case — but that doesn’t mean that there hadn’t been talks which fell through, or that Augusta hadn’t dismissed the match on other grounds.

In British history, kings marrying subjects was a fraught topic. Most medieval and early modern monarchs were married to the children of other monarchs, which kept up royal prestige, cemented alliances, and kept any one noble family from becoming too powerful. The major exceptions that would have been on anyone’s mind in the eighteenth century would have been Edward IV and Henry VIII.

Edward IV (1442–1483) was one of the major players in the Wars of the Roses, the civil wars between the houses of York and Lancaster. His marriage to a female relation of the king of France was being discussed when he secretly married Elizabeth Grey, née Woodville, the widow of a knight who had fought against him. This helped cause a rupture between Edward and the Earl of Warwick, his major supporter and a man known as the “kingmaker” for good reason, which eventually led to his downfall; the rise in social status of Elizabeth’s relations also led to discontent among Edward’s other supporters.

(Interesting little side note, here. In the fifteenth century, the Earl of March was a lower title belonging to the Duke of York and was used by Edward as a courtesy title when his father was alive. When it was later recreated, it was a lower title belonging to the Duke of Richmond and was the courtesy title Lady Sarah Lennox’s father used when his father was alive.)

The infamous Henry VIII (1491–1547) was his grandson. His decision to divorce his royal wife, Catherine of Aragon, for his subject, Anne Boleyn, sparked the English Reformation. His marriage to Anne was disastrous, ending in her execution, and he followed it with multiple other marriages to subjects, some of which ended even worse (e.g. Kathryn Howard). While much English historiography shows a bias toward Anglicanism, Henry has not gone down well in history even though he started the whole thing.

So Princess Augusta and Lord Bute would probably not have countenanced any marriage between George and Sarah, regardless of her relationship to Henry Fox — or between George and any young lady of the British aristocracy. While the fears for the stability of the crown in Queen Charlotte are vastly overstated, this is potentially something that would have made people concerned about problems down the line.

The sources referred to for this post:

The Life and Letters of Lady Sarah Lennox, 1745-1826: Daughter of Charles, 2nd Duke of Richmond, and Successively the Wife of Sir Thomas Charles Bunbury, Bart., and of the Hon: George Napier; Also a Short Political Sketch of the Years 1760 to 1763, by Henry Fox, 1st Lord Holland, vols. 1 and 2

Stella Tillyard, Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa, and Sarah Lennox, 1740-1832 (1994)

|

| Lady Sarah Bunbury Sacrificing to the Graces by Joshua Reynolds, ca. 1764; Art Institute of Chicago 1922.4468 |

Lady Sarah Lennox was one of the famous Lennox sisters (“famous” if you’re into aristocratic Georgian England, anyway): the daughters of Sarah Cadogan and Charles Lennox, Duke and Duchess of Richmond, Lennox, and Aubigny.

The Duke was the grandson of Charles II via his mistress Louise de Kérouaille; Charles II was a decent father to his many illegitimate children, granting them titles, incomes, and estates to set them up as part of the upper rank of his subjects. Charles Lennox’s father arranged his marriage to the Honorable Sarah Cadogan in a way that sounds quite familiar if you read a lot of historical romances — it canceled out her father’s gambling debt. She was 14 and he was 18, and after the ceremony Charles went on his Grand Tour; when he returned three years later, he found her enchanting from afar and then learned that they were married.

Four of their daughters survived to adulthood: Caroline (1723–1774), Emily (1731–1814), Louisa (1743–1821), and Sarah (1745–1826). All of them played a part in the social scene of their day, but it’s Lady Sarah Lennox we turn to now.

Unfortunately, Lady Sarah’s letters as published don’t begin until just prior to George’s marriage to Charlotte in July of 1761. For the background, we must turn to the stories given by her brother-in-law, the politician Henry Fox, Lord Holland, and by her son, Captain Henry Napier. His account was published in 1837, after his mother’s (and George III’s) death, as part of Fox’s memoir. He claimed that it was what his mother told him, jotted down in his personal papers.

According to him, Lady Sarah became a favorite with King George II as a spunky five-year-old; shortly thereafter, her mother died and she went to live with an older, married sister (Emily Fitzgerald, Countess of Kildare and later Duchess of Leinster) in Ireland. When she was 13, Emily passed her on to another sister - Lady Caroline Fox, later Baroness Holland. Since she was in England again, the king asked for her to come back to court, where he was annoyed that she was now a shy teenager rather than a cute young child. When the king exclaimed, “Pooh! She’s grown quite stupid!” his grandson, the young Prince George, who would have been around 20, began to feel sorry for her. This developed into a romantic attachment.

George III became king a few years later in 1760 and Sarah, now 15, was properly presented at court. This meant that she was now considered “out” in society, a young adult who could be approached for offers of marriage. George began to seek her out at visits and balls, and to engage her in conversations that hinted at his interest in her, although Sarah made sure to firmly keep to propriety. He in fact directly told her friend, Lady Susan Fox Strangeways, that he intended for Sarah to become his queen by the time of his coronation, and shortly thereafter he sort-of-proposed and she turned him down.

|

| Lady Susan Fox Strangways by Allan Ramsay, 1761; private collection |

In early 1761, Sarah fell from her horse during a hunt and broke her leg and had to stay out of society while it healed. When she returned to court, George was overjoyed, proposed again, and was accepted; rumors about it were everywhere. However, his mother and his tutor, Lord Bute, disapproved of the match because Lady Caroline Fox’s husband was the Whig politician Henry Fox (previously mentioned) - they feared that he would exert influence on George through Sarah. Although George continued to treat Sarah like a fiancée, they convinced him to marry Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz instead.

Sarah and her family only found out that he was marrying someone else with the official announcement. While Fox and others were outraged, Sarah’s pet squirrel had just died, and that turned out to be more important to her than losing the chance to be Queen of Great Britain and Ireland. She was appointed chief bridesmaid for the wedding and a similar position in the dual coronation, which resulted in a partially blind nobleman mistaking her for the new queen, to her embarrassment. While George couldn’t stop staring at his old flame, Charlotte was poised and gracious.

In the end, Sarah had no hard feelings about the matter, except irritation at George’s pretense that they were still engaged even while he was allowing plans to be made for his marriage to Charlotte.

Lady Sarah’s own letters to her friend, Lady Susan Fox Strangeways, tell her side of the story, which feels a little more tart, a little more alive, in comparison with Napier’s my-sainted-mother account. Unfortunately, we don’t have anything about the early stages of the courtship: the first letters are from 1761.

First, on June 19 — a very cryptic one that seems to be discussing how she would be allowed to respond to a proposal, and how Princess Augusta thwarted it. (The ellipses are probably in place of George’s name, as it could have been problematic if letters outright discussing marrying the king fell into the wrong hands.)

After many pros and cons it is determined I go to-morrow, and that I must pluck up my spirits, and if I am asked if I have thought of … or approve, — To look … in the face and with an earnest but goodhumoured countenance say that, “I don’t know what I ought to think.” If the meaning is explained, I must say, “that I can hardly believe it,” and so forth; if instead of that, you should be named, I shall say that you were so much confounded and astonished that I believe you did not understand the meaning; if the answer is — “I hope you do understand,” I shall say, “that the more I think of it, the less I understand it,” (I hope that won’t be too forward). In short, I must show I wish it be explained, without seeming to suspect any other meaning; what a task it is! God send that I may be enabled to go thro’ with it.

I am allowed to mutter a little, provided the words astonished, surprised, understand, and meaning are heard.

I am working myself up to consider what depends upon it, that I may me fortifier against it comes — the very thought of it makes me sick in my stomach already. I shall be as proud as the devil but no matter …

Well to-day is come to nothing for we were so near your namesake and her mistress (Ly Susan Stuart & Princess Augusta) that nothing could be said, and they wacht us as a cat does a mouse, but looks & smiles very very gracious; however I go with the Duchess Thursday, I’ll put a postscript in this of it. I beg you won’t shew this to anybody, so pray burn it, for I can tell you things that I can’t other people you know.

P.S. — My love (if I may say so) to Ld and Ly Ilchester, and compliments to the rest. Pray desire Lord Ilchester to send my mare immediately, if he don’t want it, for I must ride once at least immediately in Richmond Park. Much depends on i.t

P.S. — I went Thursday but nothing was said; I won’t go jiggitting for ever if I hear nothing I can tell him.

Sarah was very much aware of the difficulties of being the object of the young king’s romantic interest. More than that, she was prepared to walk the social tightrope required to marry him. She rehearsed scripts to bring him from vague sweet nothings to an unmistakable marriage proposal, without giving the impression that she wanted one, and she was impatient with the circumstances that prevented it — at the same time, she was unwilling to spend too long on this dance if he wouldn’t pop the question.

Here is the letter from July 7, relating how she learned about the royal wedding:

To begin to astonish you as much as I was, I must tell you that the --- is going to be married to a Princess of Mecklenburg, & that I am sure of it. There is a Council to morrow on purpose, the orders for it are urgent, & important business; does not your chollar rise at hearing this; but you think I daresay that I have been doing some terrible thing to deserve it, for you won't be easily brought to change so totaly your opinion of any person; but I assure you I have not. I have been very often since I wrote last, but tho' nothing was said, he always took pains to shew me some prefference by talking twice, and mighty kind speeches and looks; even last Thursday, the day after the orders were come out, the hipocrite had the face to come up & speak to me with all the good humour in the world, & seemed to want to speak to me but was afraid. There is something so astonishing in this that I can hardly believe, but yet Mr Fox knows it to be true; I cannot help wishing to morrow over, tho' I can expect nothing from it. He must have sent to this woman before you went out of town; then what business had he to begin again? In short, his behaviour is that of a man who has neither sense, good nature, nor honesty. I shall go Thursday sennight; I shall take care to shew that I am not mortified to anybody, but if it is true that one can vex anybody with a reserved, cold manner, he shall have it, I promise him.

Now as to what I think about it as to myself, excepting this little revenge, I have almost forgiven him; luckily for me I did not love him, & only liked him, nor did the title weigh anything with me; so little at least, that my disappointment did not affect my spirits above one hour or two I believe.

I did not cry, I assure you, which I believe you will, as I know you were more set upon it than I. The thing I am most angry at is looking so like a fool, as I shall for having gone so often for nothing, but I don't much care; if he was to change his mind again (which can't be tho') & not give me a very good reason for his conduct, I would not have him, for if he is so weak as to be govern'd by everybody, I shall have but a bad time of it. Now I shall I charge you, dear Lady Sue, not to mention this to anybody but Ld and Ly Ilchester & desire them not to speak of it to any mortal, for it will be said we invent storries, & he will hate us all anyway for one generally hates people that one is in the wrong with and that knows one has acted wrong, particularly if they speak of it. and it might do a great deal harm to all the rest of the family. & do me no good. So. pray remember this. for a secret among many people is very bad and I must tell it some.

…

I have taken a fancy to Lord Litchfield for looking shocked to see Lady A[ugusta, George’s sister] & Lady S.S. burst out laughing in my face to put me out when the former's brother was speaking to me last time.

This is again more interesting than the sanitized family story. Sarah was annoyed that so much of her time had been wasted, and that people at court would laugh at her for having been strung along by the king (or for setting her cap at him in the first place). Her anger comes through, as does her concern for the family’s reputation and her own social standing. It’s hard to fully believe the paragraph about her lack of disappointment, especially given that she was prepared to take him back if he had “a very good reason for his conduct”! But at the same time, there’s a feeling more like someone jockeying for position in a high school setting than playing at the Game of Thrones(tm) or maneuvering to secure her future.

Sarah hoped to be involved in the coronation ceremony specifically to get a good view, though she planned to be freezingly polite to George and his sisters. She accepted the offer of being a bridesmaid, but both her sister Caroline and Lady Susan felt this was a mistake — she quoted Caroline as calling it “mean & dirty”, and she was very annoyed at her for harping on it. As far as can be surmised from her letters, that ended the entire affair for her.

|

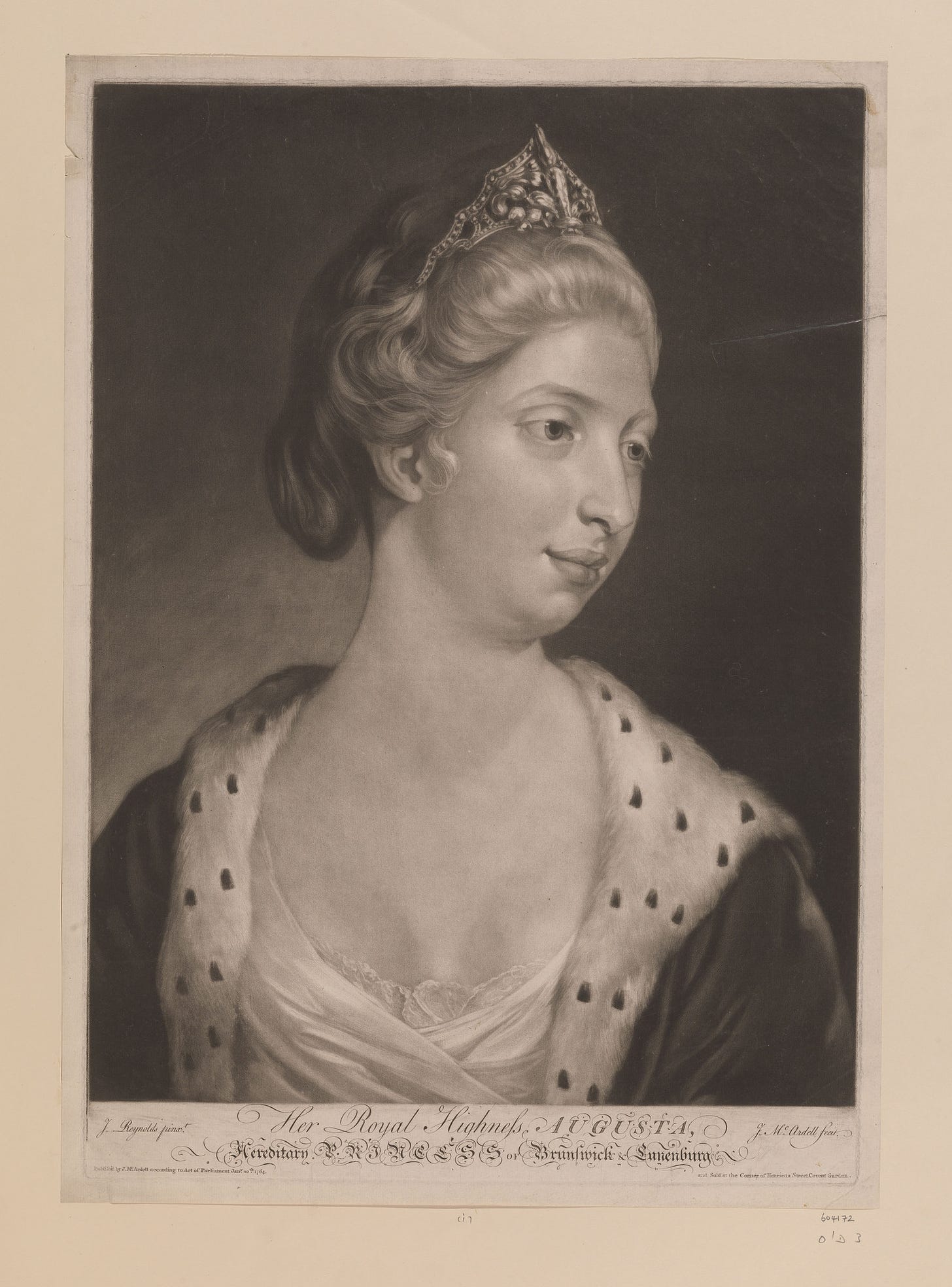

| Her Royal Highness Augusta, Hereditary Duchess of Brunswick after Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1764; Royal Collections RCIN 604172 |

Within months, Lady Sarah received another proposal of marriage, this time from James Hay, Earl of Erroll. (He has an interesting story: his father and his maternal grandfather were both attainted Jacobites, while he fought against his father in the 1745 Rising; he would have had no title as a result, but he inherited one from his mother’s aunt and took her last name along with it.) Although he knelt on the floor and wept, according to her letters, she refused him. Likely the fact that he was twenty years older than her and very freshly widowed played into all of this.

Sarah was not particularly interested in marrying for position, as her ambivalence toward George and Erroll showed. In the end, she married Sir Charles Bunbury, a handsome baronet’s heir with only £2,500 a year — an excellent income for the gentry but much less grand than Sarah was used to. She was 17 and believed herself to be the average age for marrying, so perhaps she felt her time was up and she needed to choose.

While Bunbury courted her with words of love, neither seemed to feel it for the other, and it quickly became unhappy. Sarah sought out affection and flirtation with other men, then embarked on a full-blown affair with Lord William Gordon, brother of the Duke of Gordon, which resulted in the birth of a daughter, Louisa, in 1768. The following year, Sarah and Gordon eloped (with the baby); Gordon soon abandoned her and in 1776 Bunbury obtained a full divorce from Parliament, leaving Sarah in utter social ruin.

But this was not to be the end of her social career. After the divorce, she met the Honorable George Napier, who was finally the loving partner she’d been looking for (as well as her restoration to society). They married in 1781 and went on to have eight children before his death in 1804. She died in 1826, outliving her two youngest daughters.

It seems likely to me that Princess Augusta and Lord Bute would have been looking for German princesses outside of Lady Sarah Lennox’s specific, Fox-related circumstances. There was a rumor around the time of Sarah’s accident that a marriage was being arranged with a princess of Brunswick (probably Elisabeth or Augusta of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel), but Henry Fox “had it from good authority” that it wasn’t the case — but that doesn’t mean that there hadn’t been talks which fell through, or that Augusta hadn’t dismissed the match on other grounds.

In British history, kings marrying subjects was a fraught topic. Most medieval and early modern monarchs were married to the children of other monarchs, which kept up royal prestige, cemented alliances, and kept any one noble family from becoming too powerful. The major exceptions that would have been on anyone’s mind in the eighteenth century would have been Edward IV and Henry VIII.

Edward IV (1442–1483) was one of the major players in the Wars of the Roses, the civil wars between the houses of York and Lancaster. His marriage to a female relation of the king of France was being discussed when he secretly married Elizabeth Grey, née Woodville, the widow of a knight who had fought against him. This helped cause a rupture between Edward and the Earl of Warwick, his major supporter and a man known as the “kingmaker” for good reason, which eventually led to his downfall; the rise in social status of Elizabeth’s relations also led to discontent among Edward’s other supporters.

(Interesting little side note, here. In the fifteenth century, the Earl of March was a lower title belonging to the Duke of York and was used by Edward as a courtesy title when his father was alive. When it was later recreated, it was a lower title belonging to the Duke of Richmond and was the courtesy title Lady Sarah Lennox’s father used when his father was alive.)

The infamous Henry VIII (1491–1547) was his grandson. His decision to divorce his royal wife, Catherine of Aragon, for his subject, Anne Boleyn, sparked the English Reformation. His marriage to Anne was disastrous, ending in her execution, and he followed it with multiple other marriages to subjects, some of which ended even worse (e.g. Kathryn Howard). While much English historiography shows a bias toward Anglicanism, Henry has not gone down well in history even though he started the whole thing.

So Princess Augusta and Lord Bute would probably not have countenanced any marriage between George and Sarah, regardless of her relationship to Henry Fox — or between George and any young lady of the British aristocracy. While the fears for the stability of the crown in Queen Charlotte are vastly overstated, this is potentially something that would have made people concerned about problems down the line.

The sources referred to for this post:

The Life and Letters of Lady Sarah Lennox, 1745-1826: Daughter of Charles, 2nd Duke of Richmond, and Successively the Wife of Sir Thomas Charles Bunbury, Bart., and of the Hon: George Napier; Also a Short Political Sketch of the Years 1760 to 1763, by Henry Fox, 1st Lord Holland, vols. 1 and 2

Stella Tillyard, Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa, and Sarah Lennox, 1740-1832 (1994)

Comments

Post a Comment