(

Part I of this series and

part II, if you're not coming to this from one or the other.)

Royal weddings need to be dealt with on their own, because their dress traditions differed from those of ordinary and even aristocratic women. These differences are key to understanding the context of the gown that Queen Victoria chose for her own wedding, and what exactly was the tradition she was setting with it. I know that many of you are aware that royal weddings employed silver fabrics, but I think you might be surprised at the amount of white incorporated as well.

|

| "The Ceremony of the Marriage of the Princess Royal with the Prince of Orange," 1734; British Museum Mm,3.5 |

Anne, Princess Royal, was married to William, Prince of Orange, in 1734. The bride and her eight bridesmaids were all in the "stiff-bodied gown" – a two-piece gown made with a boned, back-lacing bodice. This style of dress had been fashionable in the 17th century and had held on as English court dress until about this point (in the 1730s, a version of the mantua with a long, folded-up train replaced it), although it continued to be worn in many continental courts. The princess's was not described by

Mary Granville in more detail, but the

bridesmaids were in white and silver; the next day, the bridesmaids wore the same gowns, while the princess dressed more normally for court in a damasked white silk mantua and petticoat embroidered with gold and polychrome flowers. When her sister Mary wed in 1740, she wore a similar stiff-bodied gown,

described as having "embroidery upon white, with gold and colours, very rich; and a stuff on a gold ground, prodigiously fine," with an after-wedding sacque of silver tissue.

|

| "Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, Princess of Wales", Charles Philips, 1736; National Portrait Gallery NPG2093 |

A portrait of their sister-in-law, Augusta, Princess of Wales, was painted in the year of her wedding (1736) and likely shows her dressed in her wedding outfit: another stiff-bodied gown of silver tissue or damask. Two decades later, the future Queen Charlotte married the future George III in a stiff-bodied gown of silver tissue bedecked with diamonds, while the bridesmaids wore white silk embroidered with silver. (See Anne Buck's

Dress in Eighteenth-Century England.)

|

| "Caroline of Brunswick, Princess of Wales", Gainsborough Dupont, 1795-96; Royal Collection RCIN 404550 |

By the time Princess Caroline of Brunswick married George IV in 1795, the stiff-bodied gown - more than a century out of fashion - was probably seen as too outmoded for use, even for the most formal type of court event, and so she wore silver and white in a more conventional style - though you can see that the sleeves, trimmed with several rows of lace, were retained. The only image I'm aware of related to the 1797 marriage of George III and Charlotte's daughter Charlotte, the Princess Royal, to Frederick, then Duke of Württemburg, is

a contemporary caricature by James Gillray. The caricature shows her headed to the bedchamber dressed in a white and gold high-waisted (non-stiff-bodied) court dress.

Princess Mary (another child of George III) married the Duke of Gloucester in 1816. While her wedding clothes are not described in the

Memoirs of Her late Royal Highness Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales, the author did note that Mary changed into traveling clothes after the ceremony, "a white satin pelisse and white satin French bonnet." The wedding clothes of Princess Charlotte herself, daughter of George IV and Caroline of Brunswick, were described in great detail:

The wedding dress was a slip of white and silver atlas [a type of satin weave with very long floats], worn under a dress of transparent silk net, elegantly embroidered in silver lama, with a border to correspond, tastefully worked in bunches of flowers, to form festoons round the bottom; the sleeves and neck trimmed with a most rich suit of Brussels point lace. The mantua [train] was two yards and a half long, made of rich silver and white atlas, trimmed the same as the dress to correspond. After the ceremony, her Royal Highness was to put on a dress of very rich white silk, trimmed with broad satin trimming at the bottom, at the top of which were two rows of broad Brussels point lace. The sleeves of this dress were short and full, intermixed with point lace, the neck trimmed with point to match. The pelisse which the royal Bride was to travel in, on her Royal Highness leaving Carlton-House for Oatlands, was of rich white satin, lined with sarsenet, and trimmed all round with broad ermine.

(The other dresses prepared for Charlotte were made of white or transparent net, silver tissue, muslin, and point lace, trimmed with various types of silk, gold, and silver laces, silver and gold embroidery, and white satin.)

In 1819, Charlotte's aunt the Princess Elizabeth was married to the Prince of Hesse Homburg, and wore a gown of silver tissue trimmed with lace and silver, with a robe of silver lined with white satin; after the wedding she changed into a white satin pelisse, like her sister Mary.

After All of This

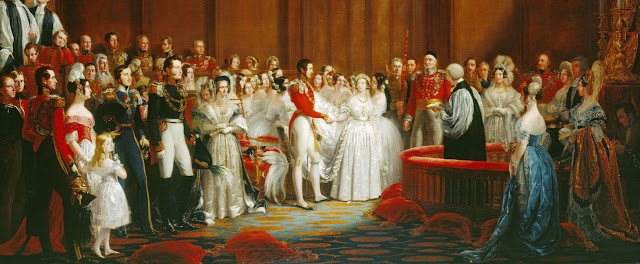

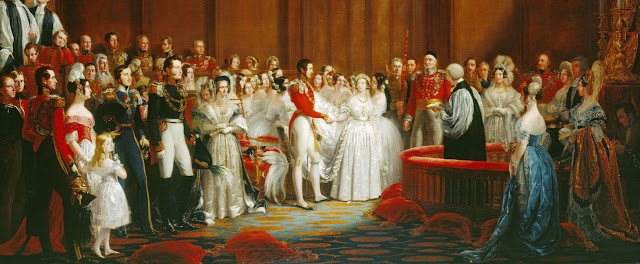

|

| The Marriage of Queen Victoria, 10 February 1840, Sir George Hayter, 1840-42; RCIN 407165 |

There was indeed a tradition of royal brides wearing silver before Queen Victoria's wedding in 1840; however, the connection between weddings and white was so strong that many of these brides (and bridesmaids) incorporated white into their dress or changed into white garments after the official ceremony. Victoria's innovation was, of course, to be a royal bride in white - visually allying her with "the people" and drawing on the old associations of white with feminine purity and innocence. Throughout her reign, Victoria strove to present herself as a wife and mother first and queen second: we can see a mirror of her choice to be "ordinary" in white in her later choice to wear an "ordinary" widow's mourning following the death of Prince Albert. While she did set a standard that her daughters, daughters-in-law, and later royal brides would follow, the episode represented a change in her own role rather than any change to the meaning of bridal white to the rest of her society.

This series is finished! If you want to help me choose what to write about in the future, please come on over and check out my Patreon.

Comments

Post a Comment