Scaling Up Patterns: A Guide (HSM #6)

It was hard for me to figure out what to write for "Out of Your Comfort Zone". My comfort zone is pretty wide, and what's outside of it - the later twentieth century - is also outside of the limits of the Historical Sew Monthly. So I tried to think more broadly about what I'm comfortable with. What makes me uncomfortable? Tutorials, definitely, because I don't do that much when it comes to historical sewing, Another thing that makes me uncomfortable is self-promotion in anything other than short bursts, and this post is essentially shameless begging for you to buy my book - Regency Women's Dress, out this autumn! - even if you normally rely on individual, full-size patterns.

This can also be seen as helping other people move out of their comfort zones. Thinking OUTSIDE the box!

---

When it comes to making historical clothing, I prefer to use patterns taken from extant garments rather than full-size ones graded for different sizes. There are a number of benefits:

The idea of this is somewhat intimidating. Just bear in mind that you're working with newspaper, which is cheap, and you'll be making a muslin, just like you would to work on any other pattern.

If you've read Cathy Hay's Corsetmaking Revolution, you'll probably find this somewhat familiar - it's based on the same concept. Mark the widest part of the bust and the waist on your pattern, either by sight or by copying it, cutting it out, taping it together, and drawing a line around it.

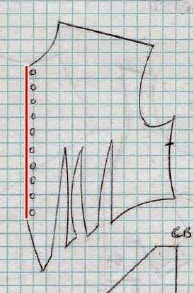

It should look something like this. Then you're going to measure those lines from the center front (accounting for the button overlap) to the center back. In this case, the finished half-bust is 18", and the finished half-waist is 12.5". In front, the half-bust is 11" and the half-waist 8.5"; in back, 7" and 4".

The next step is to figure out the proportion each piece of that is to the whole.

(piece/whole = percentage)

Front bust: 11/18 = 61%

Back bust: 7/18 = 39%

Front waist: 8.5/12.5 = 68%

Back waist: 4/12.5 = 32%

To go forward, you're going to need your own measurements in the appropriate corset. For me, that's about 19" and 14". You need to find what those percents are on your body.

(percentage x whole)

Front bust: 61% of 19 = 11.6"

Back bust: 39% of 19 = 7.4"

Front waist: 68% of 14 = 9.5"

Back waist: 32% of 14 = 4.5"

So when redrawing the back, I need to make sure the upper line is 7.4" and the waist line is 4.5" - apart from that, I'm going to try to keep the proportions about the same.

Going back up a bit, what do I mean by "keep the proportions the same"? You can see it illustrated on the back - the shoulder seam ends on the same vertical line as the side seam, so the angle line of the shoulder seam is altered to match it.

This method won't produce a pattern that's absolutely perfect, and even with the addition of your proportions you're going to have to work at fitting the muslin ... but that's something you'd have to do anyway.

Hopefully, this has been a helpful aid in your attempt at scaling up a pattern!

This can also be seen as helping other people move out of their comfort zones. Thinking OUTSIDE the box!

---

When it comes to making historical clothing, I prefer to use patterns taken from extant garments rather than full-size ones graded for different sizes. There are a number of benefits:

- The pieces are likely to fit together as they are, and I can check to make sure fairly easily since they're drawn to scale.

- There aren't any alterations made to adapt the pattern for sewing machines, modern methods, etc. that need to be reversed. (Though there are now patternmakers like Hallie Larkin and Kay Gnagey who are producing scaled-up patterns intended to be made up with period methods and/or based directly on specific garments.)

- It's much cheaper to buy a few books than a ton of patterns, plus it saves time when you want to make something new - no need to wait for the mail!

- The inevitable problems and efforts to fix them teach me a lot about the proper way to do things, and why the original seamstresses did them the way they did. Obviously, this doesn't sound like a shining endorsement, and it has the knock-on effect of making me feel useless at times, but I do also see enormous amounts of improvement between each related outfit. And each corset. Especially corsets.

It's cool to use whatever method you want to make your garb, but I've seen a lot of people say that they can't scale them up because they don't have a projector or giant copier, and they don't know how to do it by hand. Obviously it's to my benefit if you can not only look at the great pictures in Regency Women's Dress but use the patterns, but I also want to share my genuine enjoyment of messing around with graph paper and maybe open up the possibility of using Janet Arnold, Norah Waugh, Jean Hunisett, or myself (don't forget the patterns I took at the Chapman Historical Museum, which are online for free)

The most sensible way is to fully scale up the pattern as drawn, make a muslin, and fit it as you would fit any other muslin. However, sometimes - usually, when it comes to these patterns based on originals - you already know that it's going to be much too small in certain areas, and I often add in the extra width/height while scaling up. Both methods will be discussed!

The zero step is to make sure you have supplies. Namely:

- paper large enough to draw the pieces on

- I use newspaper, which is pretty cheap if you get a local Wise Shopper or some other free periodical of classifieds

- there's also pattern paper with a 1"x1" grid printed on it, which is even easier to use but costs a bit more than your recycling

- you can do this straight onto muslin, but then you have to take grain into account, plus it's harder to write on

- a ruler

- a yardstick and/or measuring tape for any bits that are longer than 12"

- a right-angled ruler

It seems like the books most frequently use a scale of 1/8":1", that is, 1/8th of an inch on the page equals one inch in real life, but not all, so check to make sure you know your scale. Corsets & Crinolines in particular seems to use a weird scale: if you're working with that one, you might want to use the printed scale to draw notches on a bit of paper to use as a ruler instead.

The first step once you have all that is to determine your vertical line. Most of the time, this is going to be the center back or the center front - even if these are meant to be on the bias in the final version, because the paper has no relevant grain.

For a side piece, a sleeve, a shoulder strap, etc. you can use any straight line. Depending on the era and sleeve, you may draw the line in the middle of the paper and go from side to side; the other pieces can usually go along one edge of the paper, saving you some drawing and cutting. Just make sure that you're high or low enough on the page not to cut yourself off.

For an example, I'm going to use the early 1860s day dress I previously posted - 1981.31.1a-b at the Chapman Historical Museum.

For an example, I'm going to use the early 1860s day dress I previously posted - 1981.31.1a-b at the Chapman Historical Museum.

After you have a line, start measuring over to major landmarks at right angles (hence the ruler). I usually start with the top. So with this pattern, it is 3.5" up and 2.5" over from the top of the center front to the corner of the neckline.

Do this all over the place. Every point can be plotted in relation to another - you don't have to find all of them based on their relationship to the main line, but it can be helpful to go back to it every so often, just to make sure you haven't messed one up. (Shown with the dotted lines.)

(I kind of overdid it to make the point. You can - should - do the front point of the bodice and the side seam, then a curve for the lower edge between them. You don't really need to do the steps between the darts, because the darts are going to change based on your own figure anyway.)

That looks really intense! But you don't have to draw lines on your pattern with different colored markers. As you do each one, plot it on your newspaper (or whatever paper you're using for this) and draw as you go. For straight lines you can just go from point to point, but with curves you probably want to check the depth on the way.

That will help you make sure they're not too shallow or too deep.

And that's basically it! From this point, you can trace it onto muslin, cut it out, and treat it as you would any other pattern that needed alteration. Mainly, of course, you'll be making them larger. These patterns are pretty much always tiny. Jennie Chancey has a very detailed guide to resizing a real-size pattern, but I'll give you my general rules after I go over the scaling-up-while-altering method.

Scaling Up While AlteringDo this all over the place. Every point can be plotted in relation to another - you don't have to find all of them based on their relationship to the main line, but it can be helpful to go back to it every so often, just to make sure you haven't messed one up. (Shown with the dotted lines.)

(I kind of overdid it to make the point. You can - should - do the front point of the bodice and the side seam, then a curve for the lower edge between them. You don't really need to do the steps between the darts, because the darts are going to change based on your own figure anyway.)

That looks really intense! But you don't have to draw lines on your pattern with different colored markers. As you do each one, plot it on your newspaper (or whatever paper you're using for this) and draw as you go. For straight lines you can just go from point to point, but with curves you probably want to check the depth on the way.

That will help you make sure they're not too shallow or too deep.

And that's basically it! From this point, you can trace it onto muslin, cut it out, and treat it as you would any other pattern that needed alteration. Mainly, of course, you'll be making them larger. These patterns are pretty much always tiny. Jennie Chancey has a very detailed guide to resizing a real-size pattern, but I'll give you my general rules after I go over the scaling-up-while-altering method.

The idea of this is somewhat intimidating. Just bear in mind that you're working with newspaper, which is cheap, and you'll be making a muslin, just like you would to work on any other pattern.

If you've read Cathy Hay's Corsetmaking Revolution, you'll probably find this somewhat familiar - it's based on the same concept. Mark the widest part of the bust and the waist on your pattern, either by sight or by copying it, cutting it out, taping it together, and drawing a line around it.

It should look something like this. Then you're going to measure those lines from the center front (accounting for the button overlap) to the center back. In this case, the finished half-bust is 18", and the finished half-waist is 12.5". In front, the half-bust is 11" and the half-waist 8.5"; in back, 7" and 4".

The next step is to figure out the proportion each piece of that is to the whole.

(piece/whole = percentage)

Front bust: 11/18 = 61%

Back bust: 7/18 = 39%

Front waist: 8.5/12.5 = 68%

Back waist: 4/12.5 = 32%

To go forward, you're going to need your own measurements in the appropriate corset. For me, that's about 19" and 14". You need to find what those percents are on your body.

(percentage x whole)

Front bust: 61% of 19 = 11.6"

Back bust: 39% of 19 = 7.4"

Front waist: 68% of 14 = 9.5"

Back waist: 32% of 14 = 4.5"

So when redrawing the back, I need to make sure the upper line is 7.4" and the waist line is 4.5" - apart from that, I'm going to try to keep the proportions about the same.

- This is where scaling up works very well for me. I'm short-waisted - really short-waisted - and short overall, so the patterns tend to be closer to my vertical proportions than modern commercial patterns anyway. If you're short-waisted, or just short, you might find that nice as well.

Going back up a bit, what do I mean by "keep the proportions the same"? You can see it illustrated on the back - the shoulder seam ends on the same vertical line as the side seam, so the angle line of the shoulder seam is altered to match it.

This method won't produce a pattern that's absolutely perfect, and even with the addition of your proportions you're going to have to work at fitting the muslin ... but that's something you'd have to do anyway.

Hopefully, this has been a helpful aid in your attempt at scaling up a pattern!

Thank you, Cassidy! Comfort zones be demmed, this is so helpful. I was going to wait til I had the bodice made and photographed to show you, but I used the Chapman 1894 wedding bodice pattern to start making a period jacket for a production of Merchant of Venice this summer. A daunting project, but what the heck? I like them! I am struggling a little bit to fit the front darts on my actress who is very willowy but doesn't have much of a waist, even in a corset. Darts seem too long and I can't figure out how to get rid of the extra plooof in the front at the chest. I am working on it, and have every confidence that persistence will win! The back and sleeve patterns, however, are absolutely wonderful. I have robbed that sleeve for two other garments Already, with a few modifications. Great use of bias!

ReplyDeleteThanks for all you're doing. Fascinating stuff,

Nancy N

I'm so happy you're getting use out of them! That's exciting, I definitely want to see the photographs.

DeleteI am SO INTERESTED in your forthcoming book, since the Regency/Federal/Empire periods are my specific area of interest. And thanks so much for this helpful tutorial. Using one of the many excellent book patterns is out of my comfort zone, since not only do you have to size them up you then have to figure out how to make it YOUR size. So again, thanks.

ReplyDeleteI hope you like it when it's published! And I hope the tutorial is actually helpful and works for other people, I'm a bit nervous that all of this only makes sense in my head.

DeleteThank you for posting this as encouragment! I have the Janet Arnold book and have used PhotoShop to scale up but I have wanted to learn this method.

ReplyDeleteI hope it works for you! It's actually kind of fun, I think.

Delete