Cabinet des Modes, 17e Cahier, 3e Figure

|

| July 15, 1786 |

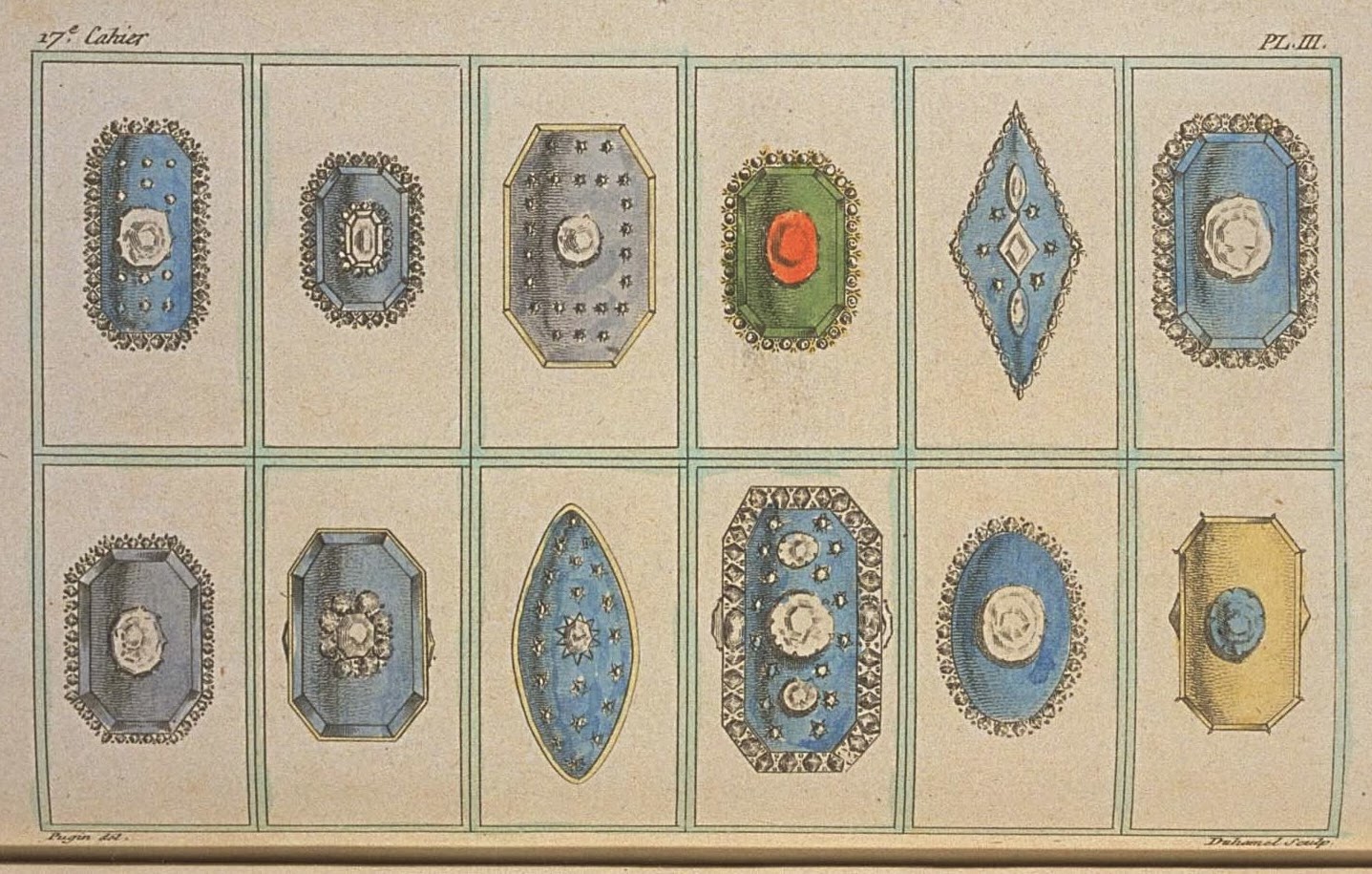

PLATE III.

A Ring chart.

M. Bourignon de Saintes, Correspondent of the Royal Society of Medicine, for several Academies, and of MONSIEUR's Museum, has made us the honor of sending us Research on Rings and other Jewels of women of antiquity, and gave us permission to put it into our Books. We will not fail to use it, to express our gratitude to him, and to get our Subscribers to see the similarities between past eras and our own.

M. Bourignon de Saintes, Correspondent of the Royal Society of Medicine, for several Academies, and of MONSIEUR's Museum, has made us the honor of sending us Research on Rings and other Jewels of women of antiquity, and gave us permission to put it into our Books. We will not fail to use it, to express our gratitude to him, and to get our Subscribers to see the similarities between past eras and our own."Wearing rings," says M. Bourignon de Saintes, "dates back to the furthest times past. The Chaldeans, the Babylonians, the Persians, and the Greeks wore rings. The Sabines also had them in the times of Romulus: theirs were similar to those of the Greeks. From the Sabines, they passed to the Romans.

"Rings were of gold, silver, copper, iron, or glass. Some were made of a simple metal, others of a mixed or alloy metal; for sometimes iron or silver were plated, or surrounded gold with iron. The first were simple and of a common metal; following that, they were made in silver and gold, and soon no others were worn, or at least not unless they were gilded.

"A ring distinguished free men from slaves, in the beginnings of the Republic: the citizens wore them of glass. The right of wearing them in gold only belonged to Senators who had satisfied some ambassadorship in a foreign Country. This practice was then permitted to other Senators, and became at last the proper and distinctive sign of Knights. In this era citizens and freedmen wore silver rings, and slaves those of iron; but after the ruin of the Republic, the gold ring was no more than a weak distinction which was accorded even to freedmen. Augustus was the first to whom they were obliged for this honorable favor: Septimus Severus extended it to simple soldiers.

"A ring distinguished free men from slaves, in the beginnings of the Republic: the citizens wore them of glass. The right of wearing them in gold only belonged to Senators who had satisfied some ambassadorship in a foreign Country. This practice was then permitted to other Senators, and became at last the proper and distinctive sign of Knights. In this era citizens and freedmen wore silver rings, and slaves those of iron; but after the ruin of the Republic, the gold ring was no more than a weak distinction which was accorded even to freedmen. Augustus was the first to whom they were obliged for this honorable favor: Septimus Severus extended it to simple soldiers."The ancients singularly varied the manner of wearing their rings. The Hebrews placed them on the right hand, the Greeks on the fourth finger of the left hand, the Gauls and ancient Britons on the middle finer. Before they were adorned with precious stones, when the face was engraved even on the plaque of the ring, they were worn indifferently on either hand; but Fashion having made a rule for the practice, they were put first on the fourth finger, then on the index, the little finger, and successively on all the fingers, except the middle one. After art had added stones, they were worn on the left hand, and by a sought-after delicacy, on the right hand.

"The Greeks and Romans multiplied them gradually, until they were worn with several on each joint of each finger; they had pushed luxury and magnificence to the point of having winter and summer fashions, and others that were only worn on birthdays. Seneca declaimed much against the vanity of women, who wore one or two inheritances on their fingers.

"The Greeks and Romans multiplied them gradually, until they were worn with several on each joint of each finger; they had pushed luxury and magnificence to the point of having winter and summer fashions, and others that were only worn on birthdays. Seneca declaimed much against the vanity of women, who wore one or two inheritances on their fingers."Marriage rings were round and plain, that is to say without any stone, and they were of iron. In later times they were gold, enriched with precious stones. The ring which the fiancé gave to his intended, was a mark of the engagement that he contracted with her, and of the power that he gave her to rule his household. Religion sanctified further this practice; for the benediction of the nuptial ring is found in the ancient Liturgies.

"Some Authors trace the origin of wedding rings to the Hebrews; they base this on a passage from Exodus. Leon of Modena however supports that the Hebrews never used the nuptial ring."

About us, we imagine that the Rings that are worn today, have only given birth to the practice of wearing the nuptial ring, whether this ring came from the Hebrews, or it only came from the earliest times of our Monarchy. We do not remember having read in our History any passage which gives its origin. This ring could be subject to as many variation, in material, as those of the ancients; it is that which we are ignorant of. But, still, we think that it is to that which rings owe their birth. The custom which the French have of taking the hand of a young person on whom a ring is seen, be it for congratulating her on her marriage, be it for the right to admire a beautiful hand, and of complimenting it, must give to women the desire of parading richness or taste. They will have first worn a single enclosed diamond, then two, then a great number of the same ring, then finally a great number of rings.

About us, we imagine that the Rings that are worn today, have only given birth to the practice of wearing the nuptial ring, whether this ring came from the Hebrews, or it only came from the earliest times of our Monarchy. We do not remember having read in our History any passage which gives its origin. This ring could be subject to as many variation, in material, as those of the ancients; it is that which we are ignorant of. But, still, we think that it is to that which rings owe their birth. The custom which the French have of taking the hand of a young person on whom a ring is seen, be it for congratulating her on her marriage, be it for the right to admire a beautiful hand, and of complimenting it, must give to women the desire of parading richness or taste. They will have first worn a single enclosed diamond, then two, then a great number of the same ring, then finally a great number of rings. This practice may have been adopted by men, that is what stuns us. Have these Messieurs pretended to admire their hands, and to kiss them? The great Bayard may have worn a ring with the device, without fear and beyond reproach, that he had made for the brave Knights who followed in his exploits to wear, it was a mark that a man could show on his hand, that Bayard had chosen. Our Great Men may thus wear a ring with a device as just as that of Bayard, and give a matching one to each man in whom they have recognized merit, and that they will have adopted, this is what we will applaud; but our men wear rings, our Turcarets, over-all, have their fingers covered by them ... We do not perceive that we should speak of Fashion, and that we take censure for it. What matter? these reflections will be put with the number of complaints, and Fashion will not go less in its train.

This practice may have been adopted by men, that is what stuns us. Have these Messieurs pretended to admire their hands, and to kiss them? The great Bayard may have worn a ring with the device, without fear and beyond reproach, that he had made for the brave Knights who followed in his exploits to wear, it was a mark that a man could show on his hand, that Bayard had chosen. Our Great Men may thus wear a ring with a device as just as that of Bayard, and give a matching one to each man in whom they have recognized merit, and that they will have adopted, this is what we will applaud; but our men wear rings, our Turcarets, over-all, have their fingers covered by them ... We do not perceive that we should speak of Fashion, and that we take censure for it. What matter? these reflections will be put with the number of complaints, and Fashion will not go less in its train.It must be confessed however that if it is a bad thing, this bad has something agreeable. It is useful at least, in that it is not the smallest branch of commerce, and, to consider it under this point of view, is necessary. Also we only criticize it a little, because we respect its effects. Wear on, Messieurs, wear a great number of them; it is the Fashion, and it is a lasting Fashion; it has as much taste as richness. Those made today have a pretty form, and this can still justify the Fashion.

They are very-large now, very different from those that were worn less than two years ago, which were only often composed of a large enclosed stone. A large diamond, a large brilliant stone is put in the middle of an oval, squared, lozenge, plain squared, eight-sectioned squared composition stone. In the middle of this composition stone, the diamond is surrounded with other fine stones, or roses, or it is alone. The composition stone is surrounded with diamonds, or roses, or pearls; or it is nude, it is all plain. If the stone in the middle is not rather large, two smaller ones are put at the two ends of the setting: it is surrounded as well with other diamonds. Most often the setting is dotted with little diamonds mounted in little stars, and these are called Rings au Firmament. If the stone is rather strong, it is put alone in the middle of the composition stone, and it is still dotted with little stars in diamond.

The lozenge settings have four sharp points, or are little marked, and hardly form long ovals. The squared are long, or are perfect squares, and are all with cut angles.

The compositions stones have a green, Sky blue, violet, puce, yellow, or grey ground.

In the place of white stones in the middle of the setting, colored stones are placed, in observing the unity, as there should be, of the composition stone of the setting with the surrounded stone. It is necessary that that of the setting matches the surrounded stone in a manner which flatters the eye, the only judge of taste. These latter ones are called, Rings à l'Enfantement. If they are large, they are for women, as for men.

You can make your choice from the Rings drawn in the Ring Chart represented in the IIIrd Plate; the colors seem to match well.

This Ring Chart is drawn from the Shop of M. Moricand, Merchant Jeweler, residing in the place Dauphine, no. 30. All sorts of works in jewelry are found in his Shop, such as Mirzas, Medallions, Crosses à la Jeannette, all in brilliants, diamonds, and roses. The Curious will also find there all sorts of colored Stones, fine, crude, or cut, Stones engraved with reliefs and in hollows, fine Pearls, together with antique Stones, of the best kind. Those who ask it of him, are sure of being very-well served.

One can also write, for Rings, to M. Granché, at the Little Dunkirk. He possesses a very-rich assortment.

Comments

Post a Comment